Published on

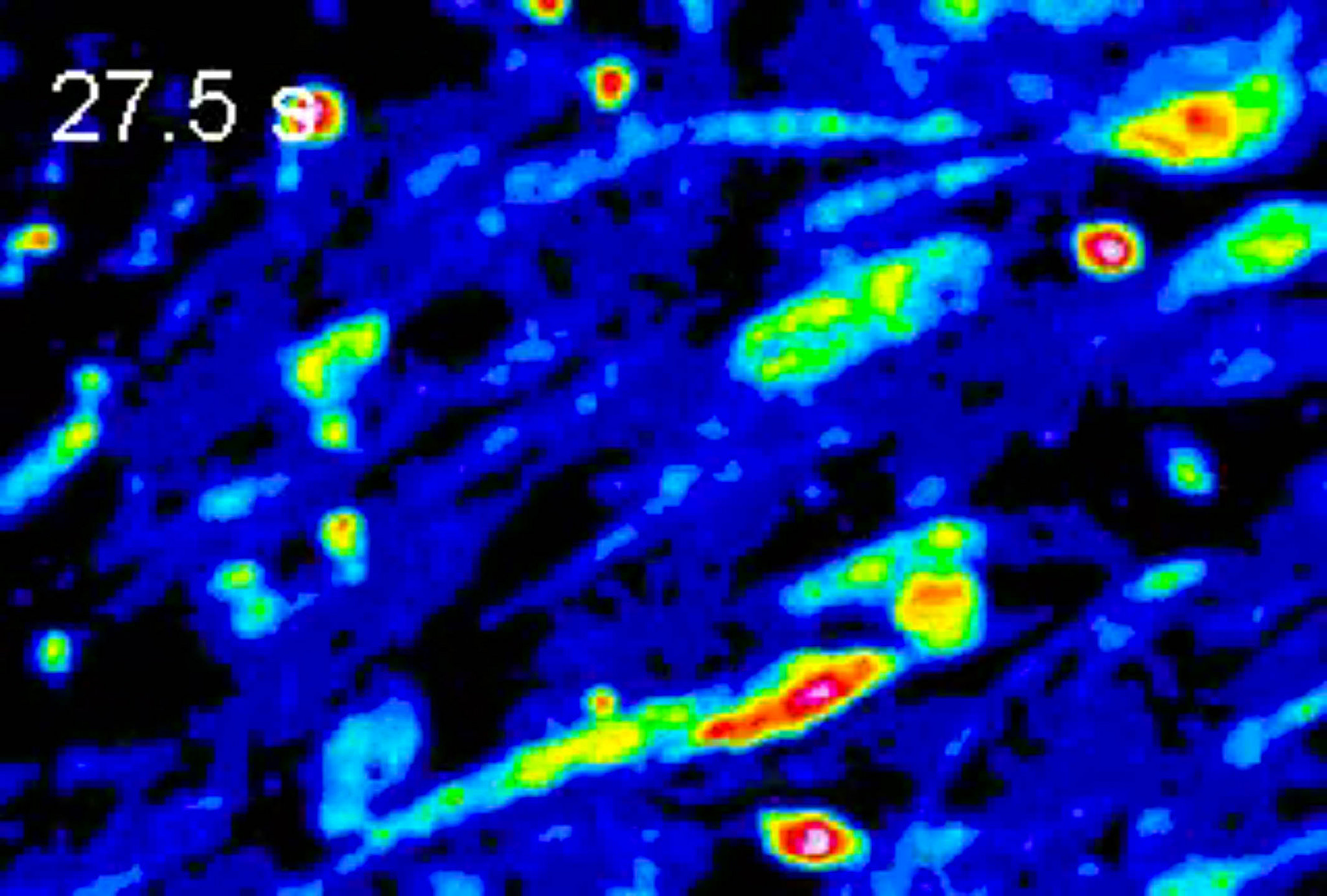

This screenshot of a supplemental video included in Genovese’s study shows cultured pork cells contracting in response to a neurotransmitter. | photo courtesy of the Nicholas Genovese

What if you could have pork without the pig? Nicholas Genovese’s cultured meat could provide a more environmentally friendly meat

By Eleanor C. Hasenbeck | MU Bond Life Sciences Center

Scientists are one step closer to that reality. For the first time, researchers in the Roberts’ lab at Bond Life Sciences Center at MU were able to create a framework to make pig skeletal muscle cells from cell cultures.

In vitro meat, also known as cultured meat or cell-cultured meat, is made up of muscle cells created from cultured stem cells.

As a visiting scholar at the University of Missouri, Nicholas Genovese mapped out pathways to successfully create the first batch of in vitro pork. Genovese also said it was the first time it was done without an animal serum, a growth agent made from animal blood.

According to Genovese, his research in the Roberts Lab was also the first time the field of in vitro meats was studied at an American university.

“I feel it’s a very meaningful way to create more environmentally sustainable meats, which is going to use fewer resources, with fewer environmental impacts and reduce need for animal suffering and slaughter while providing meats for everyone who loves meat,” Genovese said.

The research could have environmental impacts. According to the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization, livestock produce 14.5 percent of all human-produced greenhouse gas emissions. Livestock grazing and feed production takes up 59 percent of the earth’s un-iced landscape. Cultured meat takes up only as much land as the laboratory or kitchen (or carnery, the term some members of the industry have coined for their facilities) it is produced in. It uses energy more efficiently. According to Genovese, three calories of energy can produce one calorie of consumable meat. The conversion factor in meat produced by an animal is much higher. According to the FAO, a cow must consume 11 calories to produce one calorie of beef for human consumption.

And while Michael Roberts, the lab’s principal investigator, is skeptical of how successful in vitro meat will be, he said the results could yield other benefits. Researchers might be able to use a similar technique as they used to create skeletal muscle tissue to make cardiac muscle tissue. Pork muscles are anatomically similar to a human’s and can be used to model treatments for regenerative muscle therapies, like replacing tissue damaged by injury or heart attacks.

“I was interested in using these cells to show that we could differentiate them into a tissue. It’d been done with human and mouse, but we’re not going to eat human and mouse,” Roberts said. “The pig is so similar in many respects to humans, that if you’re going to test out technology and regenerative medicine, the pig is really an ideal animal for doing this, particularly for heart muscle,” he added.

While you won’t find in vitro meat in the supermarket just yet, Genovese and others are working toward making cultured meats a reality for the masses. Right now, producing in vitro meat is too costly to make it economically viable. Meat is produced in small batches, and the technology needed to mass-produce it just isn’t there yet. Genovese recently co-founded the company Memphis Meats, where he now serves as Chief Scientific Officer. The company premiered the first in vitro meatball last year, at the hefty price tag of $18,000.

“We are rapidly accelerating our process towards developments of technology that we hope will make cultured meats accessible to everyone within the not-so-distant future,” Genovese said.

Nicholas Genovese was a member of the Roberts lab in Bond LSC from 2012 to 2016. The study “Enhanced Development of Skeletal Myotubes from Porcine Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells” was recently published by the journal Scientific Reports in February 2017.