Published on

Jinghong Chen | Bond Life Sciences Center

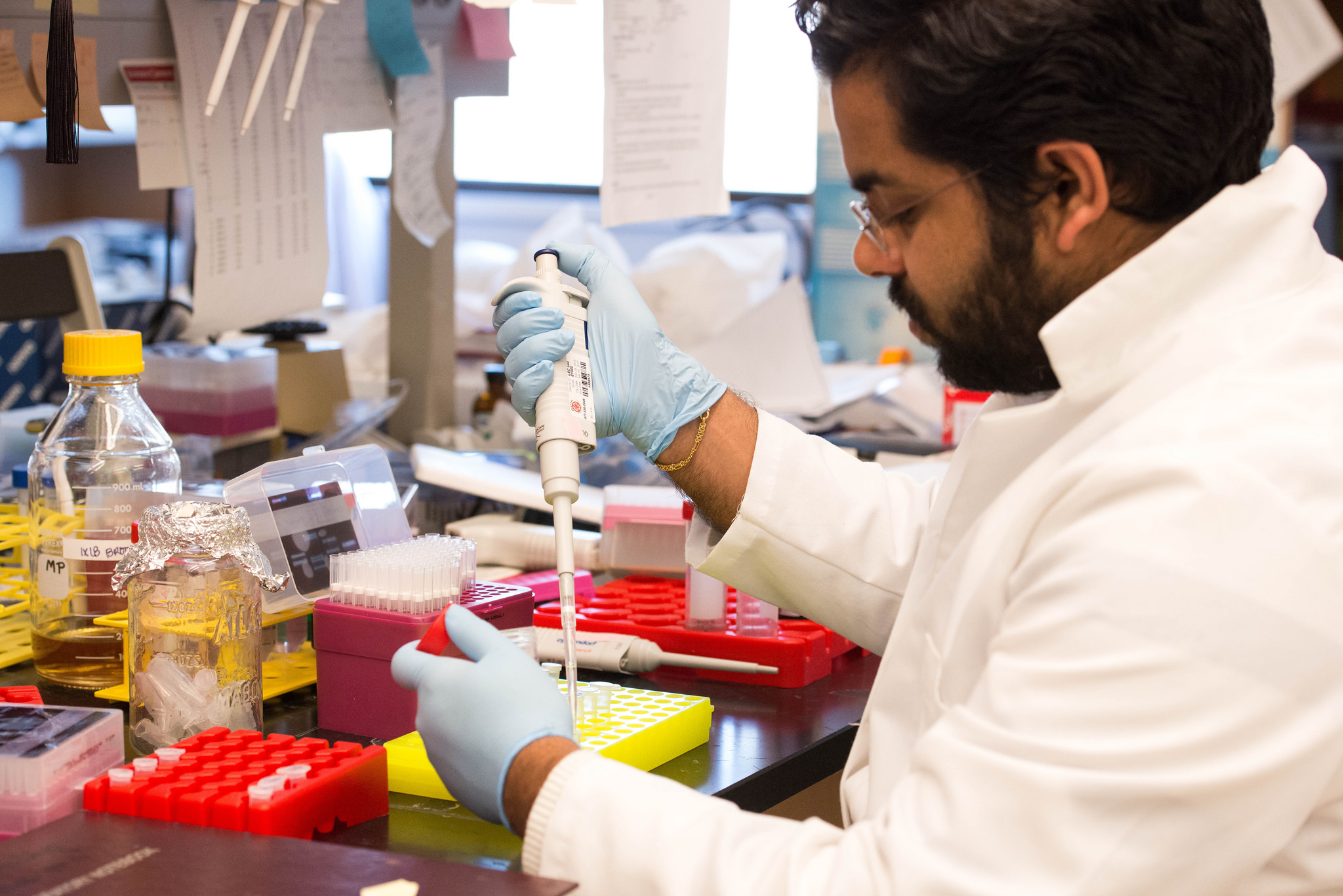

Vinit Shanbhag mixes the CRISPR plasmid DNA with cells. The lab will test whether the gene of interest has been knocked out of the cells later. | photo by Jinghong Chen, Bond LSC

It might be strange to say, but in a way the Australian soil led scientist Michael Petris to where he is now.

In certain areas of Australia, soils suffer from extremely low level of copper bioavailability, resulting in poor growth and neurological problems on sheep.

Petris, a Bond LSC investigator and professor of biochemistry who was born in Australia, now spends his time studying how copper, an essential mineral in human body, works in cells to build and maintain essential functions.

Recently published work from his lab focuses on how the ATP7A protein, one of the major proteins, cycles within the cell.

“Copper is solely acquired from diet. The absorption of copper from the intestine in the blood needs ATP7A,” Vinit Shanbhag, a Ph.D. biochemistry student at Petris’ lab and an author of the study, said. “It transports copper to different copper dependent enzymes and exports free copper from the cell to the outside.”

After exporting copper at the cell membrane, ATP7A needs to come back to its steady-state location within the Golgi apparatus of cells – via a process called retrograde trafficking. But one question baffled scientists: what are the key elements that lead ATP7A coming back?

Back in the late 90s, Petris discovered the importance of one single di-leucine in retrograde trafficking of ATP7A. For those of you wondering, leucine is an amino acid that forms the building blocks of proteins like ATP7A, while di-leucine consists of two of them connected via a peptide bond.

His team wished to identify other signals for retrograde trafficking, but one technical hurdle stood in the way— the ATP7A gene is unstable when grown in bacterial plasmids, the traditional way of amplifying genes in the lab.

Commercial DNA synthesis was the answer. This method could create artificial genes in the laboratory.

“We reasoned that if we introduced enough silent mutations into a DNA sequence, we could avoid or change the region of instability in the native sequence without affecting the encoded protein,” Petris said.

To stabilize the gene, they changed more than 1,000 nucleotides within a 3,000 nucleotides segment, and thus solving the problem of instability of the ATP7A gene. In doing so, they subsequently found that in fact multiple di-leucines that are required for retrograde trafficking of ATP7A. This approach could be used by other laboratories whose gene of interest is also unstable.

An overlooked mineral

“If you ask [people], is it important to understand iron nutrition? Is it important to understand calcium nutrition? Most people would say of course! … But, perhaps you would not get the same answer for copper, despite the fact there is a little dispute that copper is important,” Petris said.

As an essential micronutrient, copper performs central functions to develop and maintain human skin, bones, brains and other organs.

“If you don’t have enough copper in your body, you cannot use oxygen to make energy,” Petris said. “If you don’t have copper, you would not survive.”

Pregnant women who carry a mutated ATP7A gene on their X chromosome can pass it on to their children in the form of Menkes disease.

Menkes disease is a genetic disorder that results in poor uptake and distribution of copper to cells. The incidence of this disease is estimated to be one in 100,000 newborns, according to U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Infants with Menkes disease typically begin to develop symptoms during infancy and rarely live past the first few years of life. Abnormally high accumulation of copper in kidneys and low-level accumulation in the liver and brain, cause visible symptoms like sparse hair, loose skin and failure to grow.

Despite copper’s importance, it also can be a potentially toxic nutrient.

“Copper deficiency can be a problem but too much copper is also a problem. There should be a balance,” Shanbhag explained.

The liver normally stores excessive copper and excretes it into bile to release it out of the body. Yet people with genetic disorders that preventing copper excretion might suffer Wilson’s disease, leading to life-threatening organ damage.

Shanbhag said people with Wilson’s disease accumulate toxic amounts of copper in liver and other organs, causing Kayser–Fleischer rings that encircle the pigmented regions of the eye, a hue caused by copper deposits in the cornea.

Its clinical consequences differ from chornic liver failure to neurological sysmptoms like tremors, dystonia, ataxia and cognitive deteriortation.

About one in 30,000 people have Wilson disease, according to National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Starving tumors

Vinit Shanbhag mixes the CRISPR DNA with mammalian cells to specifically delete a gene in these cells in lab hood. | photo by Jinghong Chen, Bond LSC

In 2013, Petris’ lab published the first direct evidence suggesting ATP7A is essential for the dietary absorption of copper. Since then they have dug deeper into this copper transporter, and his lab now sets their sights on a greater enemy of human health — cancer.

Tumor growth requires access to large amounts of nutrients. Without an adequate supply of oxygen and nutrients, tumors fail to grow and survive. Scientists have identified that by preventing access to nutrients—for example by blocking the growth of new blood vessels—they could starve the tumor of nutrients.

Copper is a key nutrient for tumor growth. With the new-introduced system CRISPR-Cas9 — a genome editing tool to knock out specfic genes — his lab has explored how to exploit understanding of copper metabolic pathways to withhold copper from cancer cells.

“Copper starvation might be a good approach as an anti-cancer strategy,” Petris said.

Weapon of the immune system

Michael Petris, a professor of biochemistry at MU, stands with his lab. From left to right: Vinit Shanbhag, Nikita Gudekar, Michael Petris, Kimberly Jasmer-McDonald, Aslam Khan. | photo by Jinghong Chen, Bond LSC

Currently, four members study in Petris’ lab to tackle the relationship between copper and various diseases. Petris plans to expand his research to another area: the role of copper in innate immunity against bacterial pathogens.

This is the topic of Petris’ next grant. Nutritional immunity, which describes how the mammalian host withholds nutrients from the invading bacteria during infection, is very well-described for iron and zinc.

Yet copper performs differently.

During infection, the level of copper in blood actually goes up instead of going down. The immune system concentrates copper at sites of infection and within regions where the bacteria are engulfed.

“We speculate that copper is being used as weapon by the host to kill the bacteria,” Petris said. “That is the area we are trying to develop further.”

Michael Petris is a Bond LSC investigator and a professor of biochemistry. The study “Multiple di-leucines in the ATP7A copper transporter are required for retrograde trafficking to the trans-Golgi network” was published by The Royal Society of Chemistry in September 2016.