Published on

Updated on

Endocrine disruptors alter baby mice calls generations later

By Roger Meissen | Bond LSC

The sounds can seem like a mix between a bird tweet and a high-pitched scream to us, but these vocalizations that baby California mice make are essential to how they communicate with their parents and siblings.

Exposure of grandparent mice to bisphenol A (BPA) and related endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) may alter that communication in their grandoffspring, potentially affecting the communication between pups and their parents and the resulting parental care provided to them.

According to a new study, MU Bond Life Science Center’s Cheryl Rosenfeld and an interdisciplinary team of researchers from the US and Germany looked at how this communication alters from normal patterns across multiple generations of California mice.

“We specifically wanted to see if grandparents were exposed, would that affect the communication of the grandoffspring?” Rosenfeld said. “What we saw was that in some cases, some aspects of their vocalizations became even more pronounced. It might be a response to multigenerational exposure to EDCs or they might be calling more because they aren’t receiving sufficient parental care in an effort to say, ‘hey, you’re neglecting me; please pay attention and provide warmth and nutritional support to me.’”

Studies from Rosenfeld previously found that BPA caused lax parenting and neglect in first-generation mice when their parents were developmentally exposed to the chemical. This chemical acts as an endocrine disruptor and mimics the effect of hormones like estrogen in animals, altering their development. BPA is prevalent in the environment because it’s heavily used in manufacturing and leaches out of our plastics, linings of food cans and dozens of other sources.

The study showed female babies tended to make shorter calls out to parents early on after being born, but as they aged they called out more, and male babies made longer calls in early postnatal periods and spoke more as they aged. These patterns were different from controls not exposed to the chemicals.

“Exposure of the their grandparents to EDC’s is altering these grandoffspring behaviors and that could have important ramifications to human babies and how EDCs might affect their initial form of communication, crying,” Rosenfeld said. “This follow up work is clearly important because children with autism have communication deficits, as evidenced even in their early crying patterns, and altered social skills. We’re always trying to find animal models like this that might explain whether exposure to environmental chemicals is increasing the incidence of autism or autistic-like signs in animal models.”

California mice are an especially useful model for studying behavior changes, because these mice are monogamous and both mom and dad are essential in rearing their pups, similar to most human societies. This allows scientists to potentially extrapolate their behavior changes to humans.

In this study, both female and male grandparents were fed one of three diets — A BPA diet that contained an environmentally relevant concentration of this chemical, an ethinyl estradiol diet or diet free of any EDCs. Ethinyl estradiol is another disruptor found in birth control that mimics the effect of estrogen in the body. All offspring were fed the chemical-free food after being weaned off the parents. They had babies, and these grandchildren were the generation scientists looked at to study their communication.

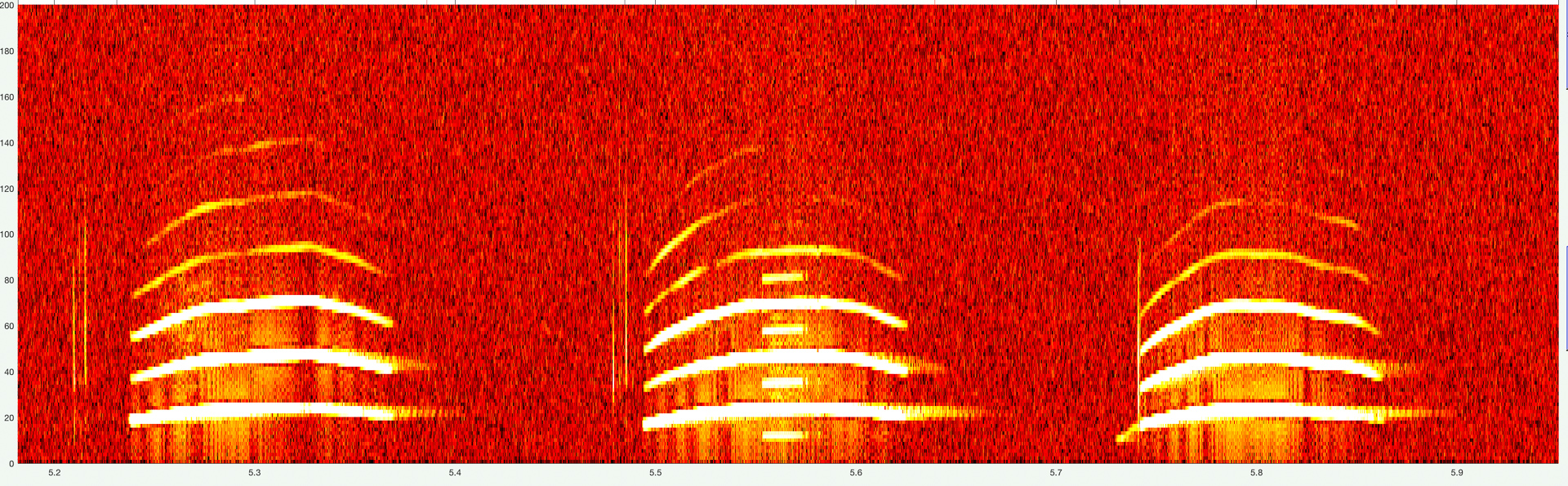

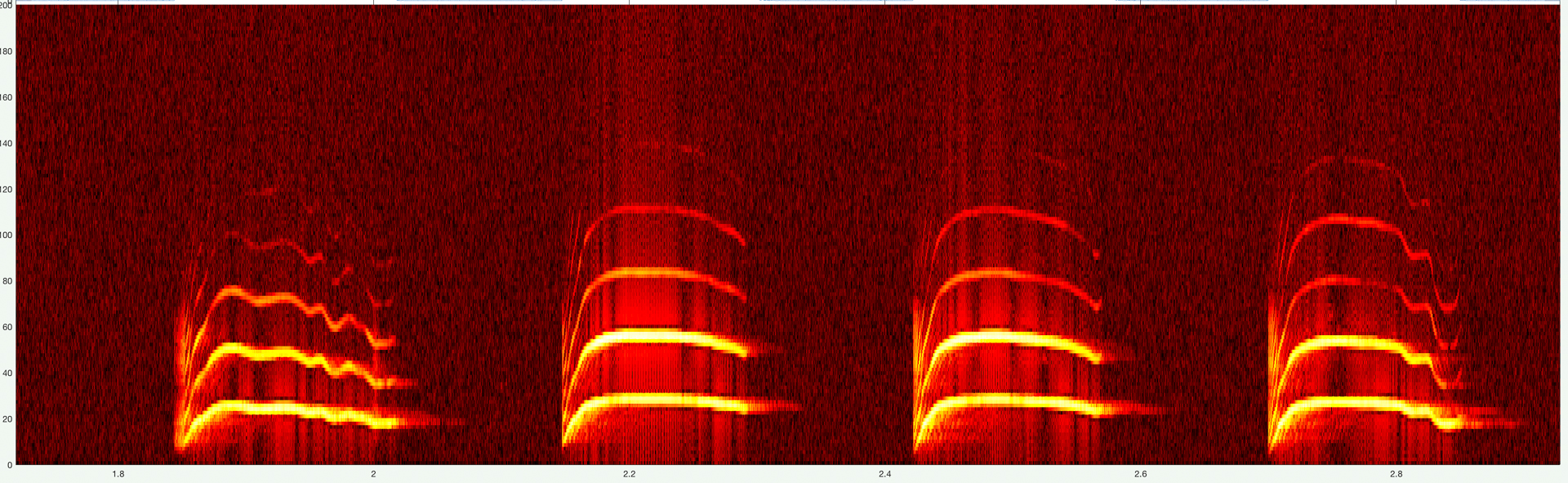

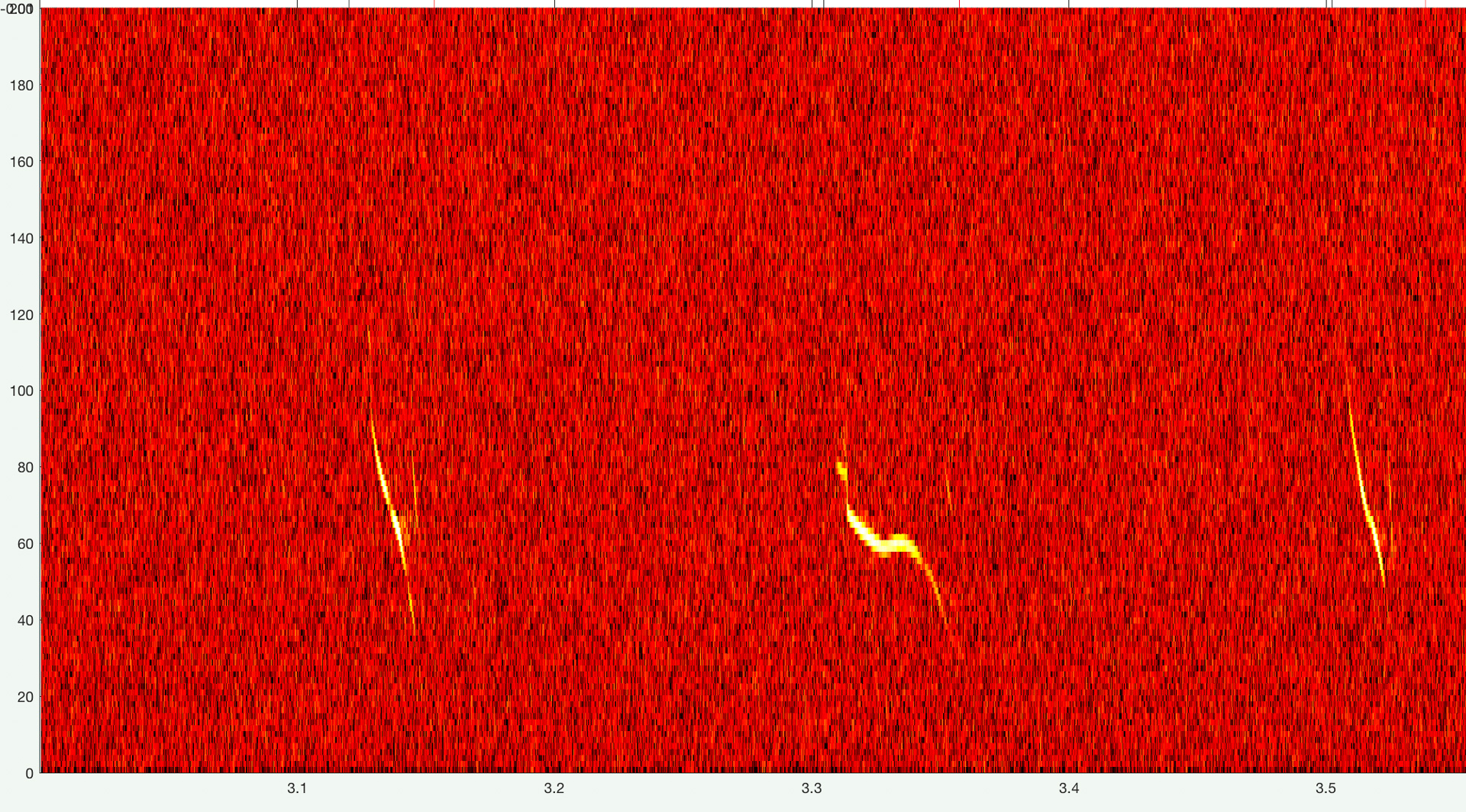

The grandchildren were recorded with special microphones that could pick up the calls of the babies in isolation booths. These sounds range from noises humans can’t even hear high in the ultrasonic range — greater than 20,000 Hertz — to noises we can mixed with sounds in the ultrasonic range. When researchers lowered the frequency of these high-pitched calls to a range we can hear they sound like a mix between owl screeches and bird tweets (how the vocalizations appear and sound are included below for the reader to decide for themselves) . They then compared them to normal mice, looking at the length of each call and the pattern of the calls, what they refer to as “syllables.” Each syllable is akin to an individual sentence or phrase in humans.

These calls from BPA exposed mice were compared to the ethinyl estradiol and the mice not exposed to any chemicals.

“We’re seeing clear traits emerge in this F2 generation with the vocalizations and I think it lends credence to the idea that these things could tamper with vocalization patterns, which are incredibly important in how pups communicate with each other and their parents, whether it’s because they are trying to get more attention from exposed parents or what we call multigenerational effects in that the exposure of their grandparents directly affected their later grandoffspring traits.”

The study, “Multigenerational effects of Bisphenol-A or Ethinyl Estradiol Exposure on F2 California Mice (Peromyscus californicus) pup vocalizations,” was funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant (5R21ES023150) and was published in the journal PLOS One June 18, 2018.