Published on

By Lauren Hines | Bond LSC

The scene of the science fair wouldn’t

be complete without the paper mâché volcano, the gymnasium full of colorful

display boards set up across a floor and the voices of students each giving

their own presentations to their parents.

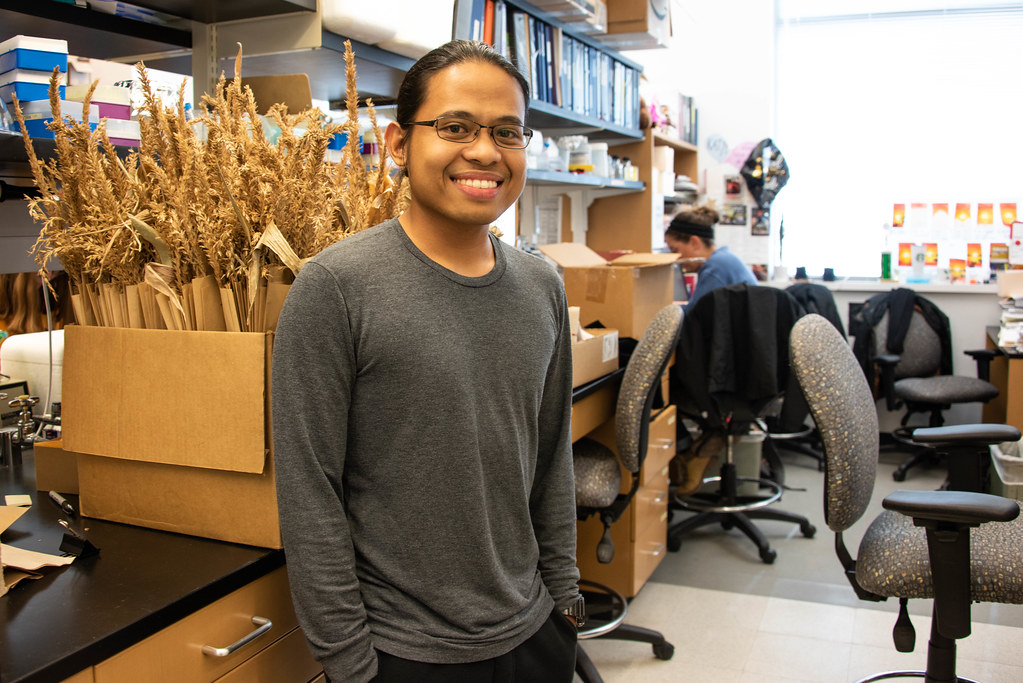

For Janlo Robil — a Ph.D. candidate in plant development genetics who works in the Paula McSteen lab at Bond LSC — his excitement for science and creativity was born in this mix of dioramas, experiments and hypotheses.

That passion has led Robil to a

place where his science and art can interact. While his experiments focus on

how the plant hormone auxin affects growth, he uses his artistic skills to

create figures and translate that science to his editors.

Robil started out as a freelance graphic artist in the Philippines where he’s from — creating logos and company designs. His inspiration comes from “natural things” and “creating shapes from what we already see as natural.”

“What’s nice about being a scientist and an artist is

that I always look for art in everything I do in my science,” Robil said.

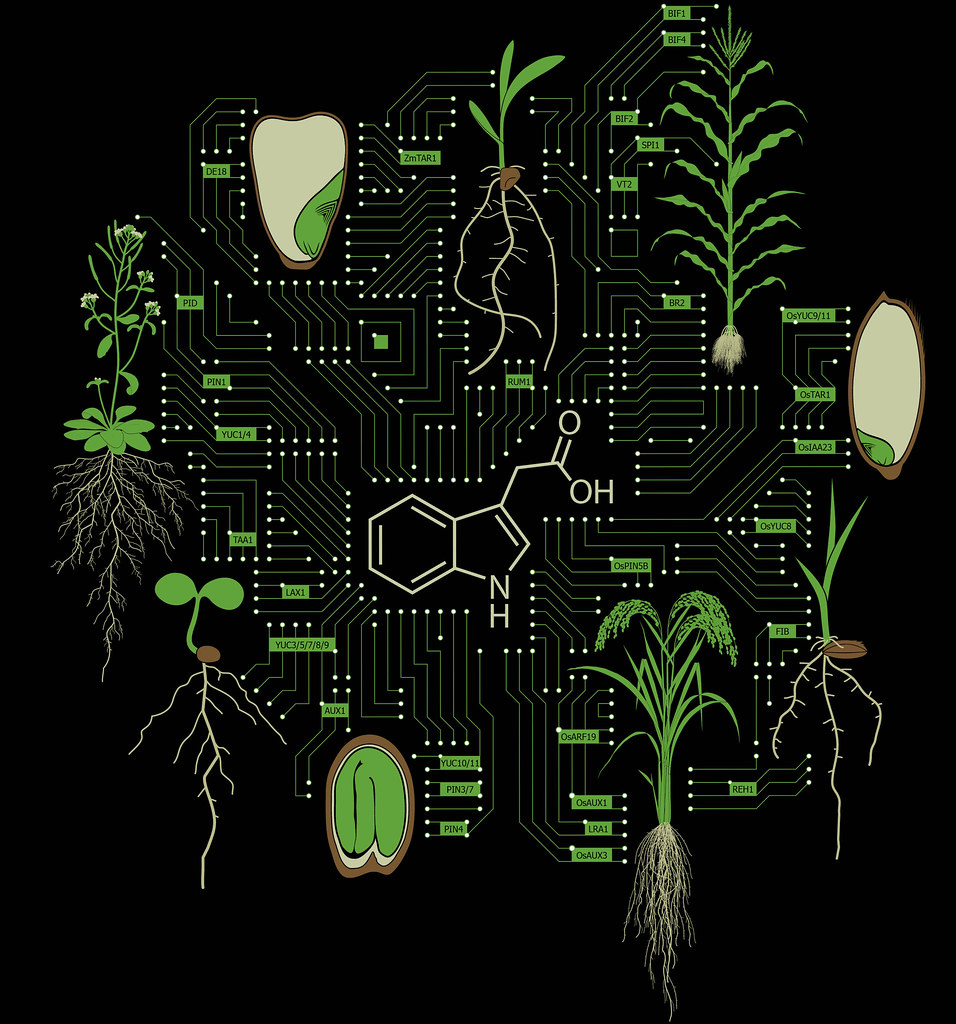

Using Adobe Illustrator as his

medium, Robil translates the science he sees onto the screen. Recently, he

submitted a piece entitled, “Auxin Motherboard” to the Kemper Museum of

Contemporary Art in Kansas City in October 2019.

Even though Robil isn’t creating

art now, he sees methods of art come up during his work in the lab.

“When I look at things in the microscope, I

pay so much attention to detail that it slows me down,” Robil said. “The same

is true when I am working in Adobe. I am very systematic about it. I feel like,

in my head, I have an assembly line on how things are going to be done. I know

a lot of artists are a lot like that. They are very organized, and they are

very systematic…. Some of the technical stuff I bring to art, while I also

bring some of my creative stuff to my science. So, there is a very good

symbiotic relationship between the two.”

According to David Epstein, science journalist and

author, scientists in general are no more likely to have artistic hobbies than

the general public, but researchers at UCLA continue to be intrigued by the parallels and

intersections of art and science.

“I see evidence of the interdependency of art and science

every day. Just last week I had a wonderful conversation about a symposium on

the physics of music,” said Pat Okker, the dean of the College of Arts and

Science.

Carlos Rivera — a fourth-year graduate student who studies brain biology in Tucker Hall — is similar to Robil in his love for both art and science. In high school, one of Rivera’s drawings was chosen for the Missouri Fine Arts Academy.

“I

always like to incorporate art into all the things I can do,” Rivera said. “I

haven’t done it in a while, but when I first started off here at Mizzou I was

taking pictures of brains, and in order to get good quality pictures you kind

of have to know how things contrast against each other.”

Rivera

would take pictures of fly brains, which required special instruments and

precision. Now, Rivera is working on a mural of R2D2 shooting glial cells

instead of lasers. A glial cell is a part of a neuron that provides support for

the neuron, and scientists are still figuring out the intricacies of their

function.

In

order for scientists to make more discoveries, they need to tap into their

artistic sides.

”Just

in general, when you’re an artist you have to learn how to think creatively and

a lot of scientists think that just comes with learning science, but you have

to learn how to be creative sometimes,” said Katherine Guthrie, a graduate

student working in the McSteen lab at Bond LSC. “So, when you have an art

background, it’s a lot easier to think outside the box when you’re thinking

about experiments or thinking about possible outcomes or planning for the

future.”

Guthrie works

with Robil in plant development genetics where they study how interrupting the

auxin hormone pathway affects development. By understanding what it looks like

when it’s broken, they can figure out how to make sure the pathway works best.

On and off for the past 10 years, Guthrie has also been teaching art classes of

every medium in school and studios.

”The

reason I’ve always loved art is because most people feel like they can’t do it

and when they find out they can, it’s like this glorious epiphany like, ‘Wow!

This is cool. I just made that.’” Guthrie said. “The reason I like science is

because you get that epiphany, and the reason I like art is because you get to

share that often.”

When

art and science get the opportunity to interact, those outside of the

scientific community are given a bridge to see what’s so exciting.

“I’m

now realizing the reason I am excited about science fairs is that it’s also an

opportunity for me to show my creativity,” Robil said. “You see these kids

making volcanoes like every time in the science fair, and I think one of the

reasons why they’re so keen to make these things is that they can also show how

creative they are and also show the scientific aspect of it. So, there are

people who are really really technical, but then I think when you add

creativity to the technicality of science, that’s when it gets really

interesting for me.”