Published on

Updated on

Marc Johnson collecting pellets in his lab. | photo by Becca Wolf, Bond LSC

By Becca Wolf | Bond LSC

There is not much thought that goes into using the bathroom. You do your business, flush, and wash your hands. It is just a part of the daily routine.

Recently though, human waste has become a golden nugget to researchers. In fact, waste from toilets throughout the community are contributing to figuring out where the next COVID-19 outbreak could happen.

And Marc Johnson, Bond Life Sciences Center principal investigator and MU professor of molecular microbiology and immunology, is the person figuring out how this human waste can be an asset as he processes samples from the sewer systems of more than 70 communities across the state.

A map of the sewersheds Marc Johnson’s lab receives samples from. | map contributed by Marc Johnson

These samples may be able to serve as the canary in the coal mine before large outbreaks strike in a community, allowing health officials to prepare for and potentially prevent the spread of COVID-19.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, appears in wastewater several days before an infected person shows symptoms, so Johnson wants to find a faster way to test for the virus.

“We’re very good at predicting what’s happening right now based on samples we collected five days ago,” Johnson said, “We are predicting the future, we just don’t know what our prediction is until the future is actually here.”

This data may not seem helpful, however, it proves that the COVID-19 case numbers are accurate and, if acted upon quickly, can prevent an outbreak in a concentrated population such as prisons or schools.

“With the students, when you’re talking about patients that don’t necessarily know they’re infected, it can be really helpful to have a heads up that this dorm has some infections even if they don’t know it,” he said.

Testing wastewater for SARS-CoV-2—an RNA virus—consists of two phases. Phase one is obtaining the sample and phase two is RNA extraction.

Starting phase one, Johnson receives a 24 hour composite from a wastewater testing facility, “So that no matter when, it doesn’t matter whenever people go, as long as they go once a day we’ll catch them,” he said. This gives his lab a representative sample of the population.

Once the sample is taken from a wastewater treatment facility, it is put into a courier system that brings it to the state lab in Jefferson City, Mo. After it arrives there, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources brings them to Johnson’s lab at Bond LSC so he can begin phase two, RNA extraction.

In Johnson’s lab, the samples are put through a filter that nothing bigger than a virus can get through. This eliminates the solids and other bacteria in the wastewater. Next, a chemical is added that allows the viral particles to stick together so they can be pelleted.

This is then put in a centrifuge and is spun for a few hours to get a small, invisible pellet. RNA is then extracted from this pellet in a QIAcube, a robot Johnson’s lab purchased for this project. The QIAcube is the same robot used by the Missouri Department of Health Services for COVID-19 testing in their own facilities.

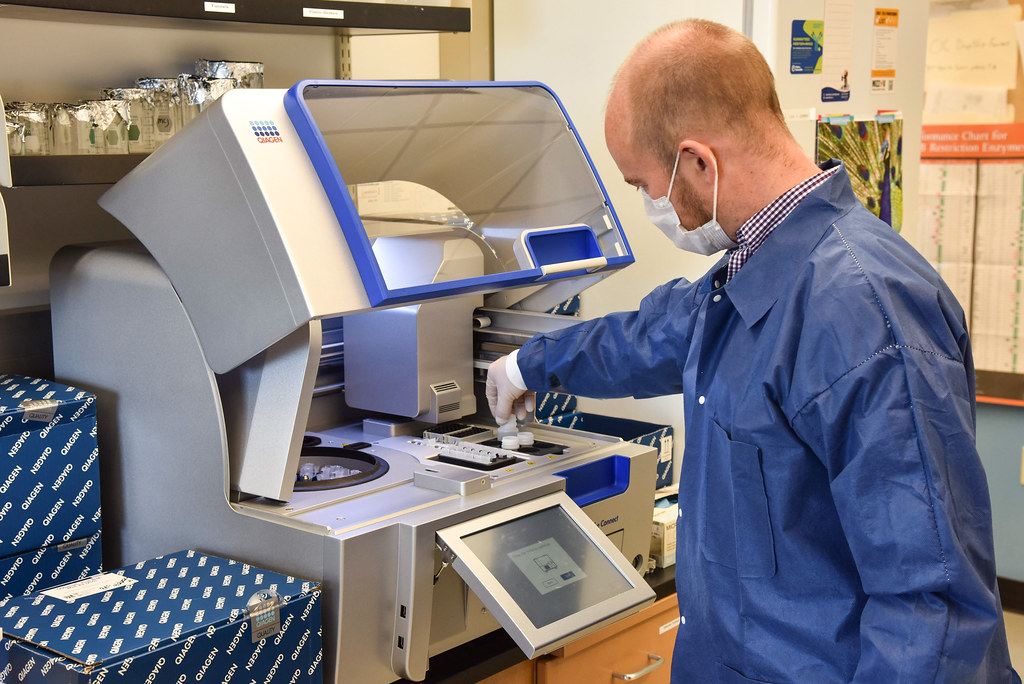

Marc Johnson placing the samples in the QIAcube. | photo by Becca Wolf, Bond LSC

After Johnson extracts the RNA, the samples are sent to Chung-ho Lin, MU research associate professor at the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, who continues testing.

This whole process takes about five days.

Johnson hopes that test results will soon go public so people have an idea of where outbreaks are, although reading the data can be confusing.

Said Johnson, “I think we all agree we’ll be better if we put the data out the way we want it to be seen, because it’s just when you look at the raw numbers, without understanding how to interpret it, you can make any conclusion you want.”

It will be a learning curve for the public to be able to understand the data. Johnson even struggled with it at first, “We learned this lesson the hard way,” he said, “I freaked out several times where I thought I had just discovered Armageddon going to our state, but you have to put it in perspective. When you figure out how much it actually takes to get a signal and how big the sewer shed sample is, it’s like, ‘No okay, that’s normal.’”

Along with other testing sites, Johnson’s lab has been testing several universities and colleges in the state, including MU. With time and improvements, it is realistic that his lab will be able to predict the number of infected patients in an area.

“It’s a crap ton of work,” Johnson said, “But it’s kind of interesting. It worked far better than I would have expected.”

While research on COVID-19 was not on Johnson’s agenda earlier this year, he has been trying to have fun with it.

“The puns are unending,” he said, “There are just so many great puns I’ve gotten out of it.”

“It’s serious research but it’s nice that the topic has gotten a little bit of levity.”