Published on

Arabidopsis may just look like a small, kelly-green weed to the naked eye, but this plant holds a particular importance in the lab.

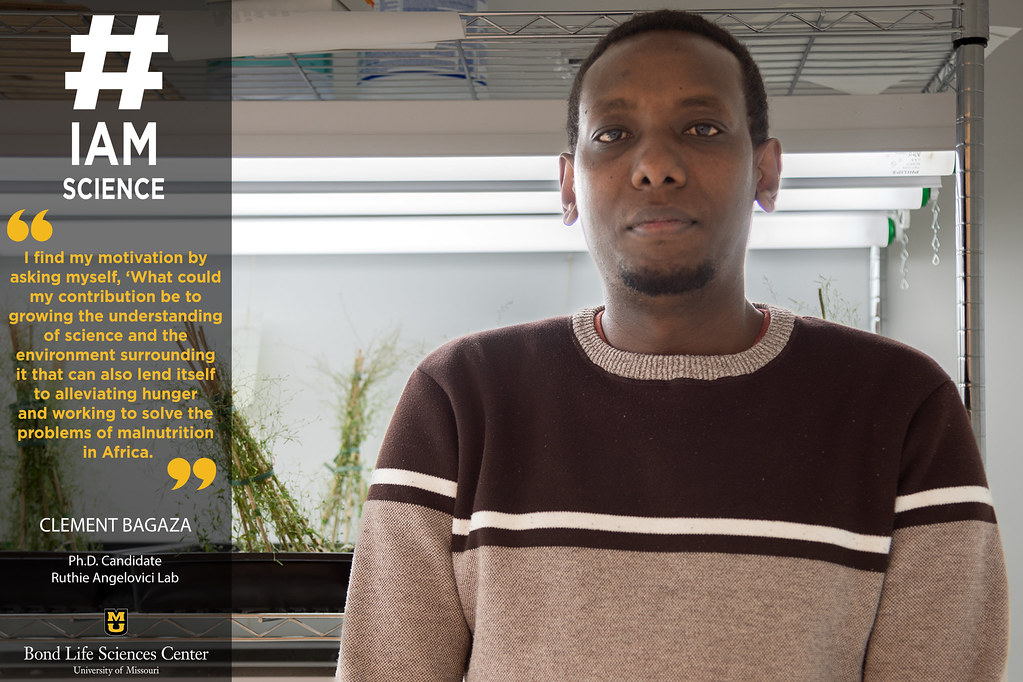

For first-generation college student, Clement Bagaza, it’s part of why he moved to the United States. Coming from Rwanda, Africa, he found an opportunity to study plants and experience a different lifestyle than the one he would have had back home. He now studies seed amino acid regulation in the Ruthie Angelovici lab at Bond LSC.

“When I came here, I didn’t know where to go. I thought working at a school or research area would give me the chance to be connected to professors and be involved in academic and research work, which was really important to me,” Bagaza said.

Amino acids are the individual pieces that form proteins. Protein molecules are building blocks of our body, and they play several other roles in our life such as: catalyzing chemical reactions in our body, controlling the expression of our genes, helping our immune system, and performing many more functions.

The Angelovici lab works to understand the genetical basis of the metabolism of amino acids in seeds. The focus of the research goes towards Essential Amino Acids (EAA), which are those that human and animals cannot make. EAAs are only obtained from eating plant products, such as grains, but their levels are lower in the grains of major crops, so the Angelovici lab hopes to be able to increase their levels in order to improve their nutritional value.

In the Angelovici lab, they mainly use Arabidopsis plant as a model plant to study the amino acids. Arabidopsis is a small plant with a short lifecycle, that does not require a big area in order to grow and prosper. Scientists often use this plant in their research with the eventual goal of transferring this knowledge to crops such as corn, soybean, and others.

Bagaza worked as a technician for Angelovici from 2016 to 2018, and afterwards decided to continue his education pursuing graduate school. He is now a Ph.D. candidate in the Angelovici lab.

The idea of performing experiments on animals made Bagaza uncomfortable, so he made the decision that plant science must be the best field for him.

Bagaza is constantly entranced by the nuances that he finds in the lab and how they lead to larger discoveries.

“It’s amazing to me to understand how genes work and how we genetically transform plants. The motivation came from my fascination with it all,” Bagaza said.

From a small town in Rwanda, Bagaza did not see science as an opportunity for him until after his childhood years had come and gone.

“I couldn’t build a motivation to play with science as a kid because nobody was doing science in my family and in the community in general,” Bagaza said.

He first discovered his love for science when introduced to biology in college. Bagaza earned his bachelor’s degree in biological sciences from the Kigali Institute of Sciences and Technology in Rwanda and his master’s degree from the University of Missouri – St. Louis.

He finds his research to be one that keeps him connected to where he came from. With increasingly high rates of malnutrition and hunger in Africa, Bagaza hunted for a position that could impact this issue.

“I find my motivation by asking myself, ‘What could my contribution be to growing the understanding of science and the environment surrounding it that can also lend itself to alleviating hunger and working to solve the problems of malnutrition in Africa,’” Bagaza said.

As Bagaza began to pursue this goal and develop a life here, it has proved to be much different than the life he would have led in Africa.

“There are a lot of challenges here, as there are a lot of challenges back home, but they are a little bit different because the basic things that people need in Africa, people have access to them here,” Bagaza said. “You lose some opportunities by living there, but you also lose something here because of it being a different society. For example, my kids will have the opportunity to be exposed to good education here.”

He spends his weekends with his wife and children, mostly going to the park or just being outside as much as possible. During basketball season, though, Bagaza can be found watching games at home, calling it his “sole hobby” during that season. He finds these activities help him relax and unwind from a day in the lab.

Bagaza’s career in science is constantly evolving as he continues to work towards his Ph.D. and considers postdoctoral fellowships or jobs elsewhere in the industry.