Published on

Updated on

By Sarah Kiefer | Bond LSC

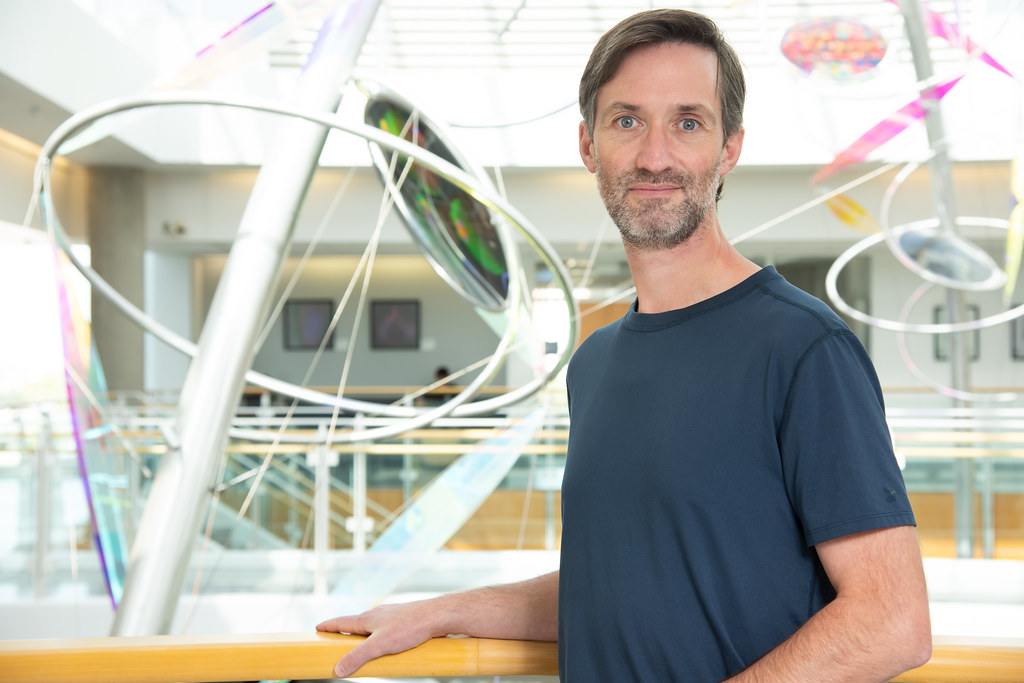

Marc Libault only ended up one floor up from his old stomping ground in his recent move.

Libault — the most recent MizzouForward hire at Bond Life Sciences Center — returned this fall to bring his expertise in plant single cell biology to MU.

“What is exciting about this research is its innovation to generate a new knowledge in crop science; we’re the first group in the world to develop a very broad application of single cell biology in plants,” said Libault, Bond LSC principal investigator and professor of plant science and technology in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources. “I was excited to come back here to continue to work on solutions at the single cell level notably by working in collaboration with experts in proteomics, metabolomics, and phenomics at MU.”

Single cell biology is exactly what it sounds like: singling out individual cells in a plant in order to reveal their unique molecular features and mechanisms. This field can help scientists better understand the functions of different genes and proteins.

“If you want to engineer a complex machine such as a car, to enhance its performance you need to first understand the nature and the contribution of each part and how they work together,” Libault said. “In plants you need to understand how each gene contributes to the biology of the cell and how each cell plays a part in the entire plant before creating meaningful genetic strategies to enhance crop biology. Having this more accurate picture allows us to enhance our current knowledge in plant and cell biology.”

While cutting and chopping are more common descriptors in cooking, researchers in Libault’s lab chop a plant sample in order to isolate the nucleus of the cells to study gene activity. His lab also focuses on spatial transcriptomics, a process that looks at how cells use their genes within the organs they inhabit. If they can understand the contribution of each cell in the plant and how they are interacting with one another, they can grasp how they work together to respond to environmental stressors.

“In society, each individual has unique competences and expertise. They work together to accomplish one goal. That’s similar to cells with unique functions working together in an organs to support its function,” he said.

By pooling this information together, they hope to identify important regulators that control how other genes are expressed then manipulate those molecular chains to see how the plant improves.

Libault is not exactly a newcomer at Mizzou.

Back in 2005, Libault came to MU from Paris, where he grew up. He worked as a postdoc in the Gary Stacey lab until 2011 when he became an assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma. He stayed there until 2017 when he moved into an associate professor position at the University of Nebraska. He got his bachelor’s degree from Denis Diderot University in molecular and cellular plant physiology and his master’s degree from Pierre et Marie Curie University in cellular biology and physiology. He went on to earn his Ph.D. in molecular and cellular plant physiology from Paris-Saclay University.

But, Libault’s last 20 years of research have been focused on understanding the mechanisms controlling gene activity including the role of epigenetics — the study of how environment and behavior change the way your genes work — helping him tackle questions like “how does the expression or repression of genes change from cell to cell?” This gives him a unique perspective as he learns to recognize the systems behind gene activity and apply that to his work on a single cell level.

The interaction between roots and bacteria is one of the areas of exploration of the Libault lab at the single cell level. In legumes like soybeans, bumps called nodules grow on the plant roots to facilitate the relationship between plant and bacteria. This nodulation gives the bacteria a place to live while it converts atmospheric nitrogen into food for itself and the plant.

“The bacteria capture the atmospheric nitrogen and convert it into a source of nitrogen supply for the plant,” Libault said. “In return, the plant will give sugar to the bacteria, which is why the two help each other.”

Outside of the lab, Libault enjoys watching Formula 1 racing or movies from the ‘70s and ‘80s in his free time. He is also interested in keeping up with French and European news. Although his balance between work and home life can become challenging at times, when things get hectic Libault prioritizes family time with his wife and three teenage boys as they continue to settle into Columbia after a few years apart.

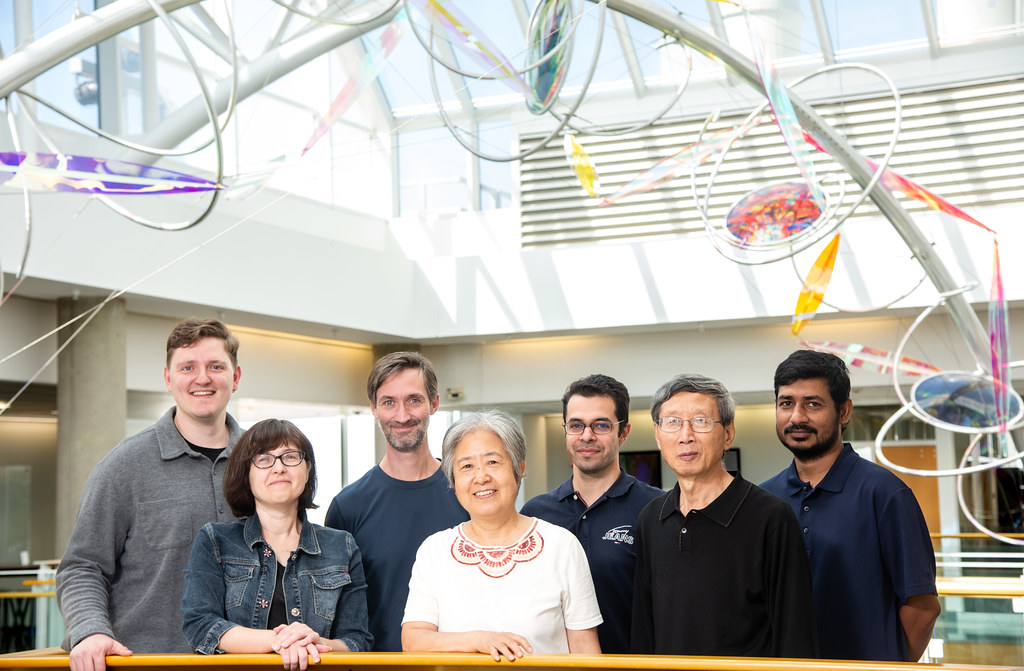

Libault has been able to hit the ground running in his lab because much of his team made the trek south with him from Nebraska in September.

Libault’s work necessitates collaboration to bring all the pieces together, and that’s what drew him back to MU.

“I know how collaborative the university and the researchers working here are, so that was a strong motivation for me to come back here and continue that kind of collective work,” Libault said. “What we have developed has been highly successful and that’s fun, but what’s next? What more can we learn? This is just the beginning of my next 25 years of research.”

MizzouForward is a transformative, $1.5 billion long-term investment strategy in the continued research excellence of the University of Missouri. Over 10 years, MizzouForward will use existing and new resources to recruit up to 150 new tenure and tenure-track faculty to address some of society’s greatest challenges. Investments also will enhance staff to support the research mission, build and upgrade research facilities and instruments, augment support for student academic success, and retain faculty and staff through additional salary support.