Published on

By Lauren Hines | Bond LSC

From developing a question to discovering a potential solution and putting it into practice, the journey from research to practical application is a long one. Nevertheless, each step brings that solution one step closer to reality.

Shift

Pharmaceuticals — the brainchild of Bond LSC’s Chris Lorson — has taken another

of those steps with a new patent issued last month and meetings with the Food

and Drug Administration in October 2019.

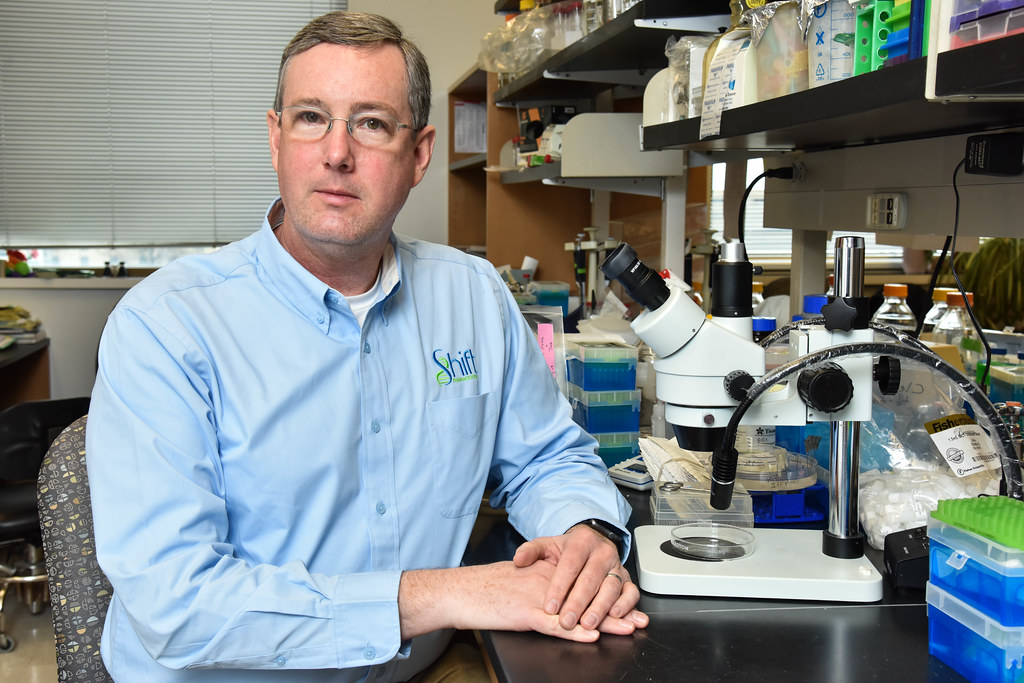

Lorson

— a Bond LSC primary investigator, professor of veterinary pathobiology and

associate dean for research and graduate studies for the College of Veterinary

Medicine — co-founded Shift three years ago in March 2017 after Lorson’s lab

had a breakthrough in his research on the genetic disorder, Spinal Muscle Atrophy

(SMA). He worked with Mizzou’s Technology Advancement Office and

entrepreneur-in-residence Steve O’Connor to dive into this business endeavor.

“Mizzou does a great job of supporting entrepreneurial activity, and

working with Sam Bish has been astounding,” Lorson said. “He really lowers the

hurdles and helps take care of the business stuff on the MU side.”

After

developing the new technology, Lorson went to Sam Bish — the senior licensing

& business development associate in the Technology Advancement Office (TAO) within the Office of

Research — to help

protect the discovery. As a faculty member, Lorson shares the rights to his

discoveries with the university since he used its resources and funds. The

initial funding for this project came from Cure SMA, a non-profit patient

advocacy group focused upon SMA. Through licensing and patenting the

technology, Shift is allowed to commercialize it even though the

university owns it.

With

the university’s help, this product moves closer to the clinic and those with

SMA are a step closer to healing.

SMA

is a genetic disorder that develops in children missing the survival motor

neuron-one gene. The disorder is the leading genetic cause of infantile death

worldwide and causes muscle weakness, respiratory failure and premature death.

SMA

is caused by the loss of a gene called SMN1. Humans have a “back-up” copy

called SMN2. SMN2 does not make enough SMN protein to prevent disease but has

been the focus of considerable interest for drug development within the SMA

field. The compound that the Lorson lab developed targets SMN2, causing SMN2 to

be “turned up” so it makes high levels of SMN protein, like SMN1. In

pre-clinical models, a single dose can extend survival ~800%.

The

compound is an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO), which is a synthetic string of

nucleic acids that bind to a sequence of the SMN2 gene. Normally SMN2 produces

a protein that has an important region that is missing. This compound forces SMN2

to make the “normal” full-length protein which would prevent disease

development.

Highlighting

the promise of personalized health care and the impact of large-scale

interdisciplinary collaboration, this type of research is part of the

University of Missouri System’s bold NextGen Precision Health Initiative. The

NextGen Initiative unites government and industry leaders with innovators from

across the system’s four research universities in pursuit of life-changing

precision health advancements.

“The university is not in the business of selling products. That’s

just not what the university does,” Bish said. “The goal with every university

technology disclosed to TAO is to get industry to commercialize it. This is what

I call the ‘Three-way win.’”

The

company wins because they produce a commercial product. The license helps money

go to the university, and the university shares some of what they received with

the inventors.

Now,

Shift is at the commercializing stage.

“Everything before 2016 was to find the lead compound,” Lorson said.

“Everything after 2016 is to prove that it’s safe and efficacious.”

Shift still needs to further develop the technology prior to submitting

it to the FDA and starting clinical trials.

Luckily,

it’s not expected for a company to fully develop a product to the market. Big pharmaceutical

companies often partner, acquire a company or license the technology after a

start-up like Shift Pharmaceuticals does the legwork to show progress and

potential.

Bish

attributes the success to the amount of money, or non-diluting capital, Shift

has raised and how Lorson created the company.

“Dr. Lorson was very smart in the way he went about this,” Bish

said. “He realized he needed partners to get this company on its feet. Some

people will say, ‘Well that shows weakness. You didn’t know how to do it on

your own.’ To me, that shows wisdom and strength because nobody knows his

science like he knows it, but there are other people that know business and

what it takes to get successfully launch and develop a biotech company that he

may not have.”

Even though Shift has far to go to make the new technology

available to those with SMA, Lorson recognizes the work that has gotten him and

his team to this point.

“Having been in the field for 20 years, it’s exciting to see it

developed,” Lorson said. “Having known many families with SMA and getting to

see them every year for 20 years, it’s exciting to see progress being made in

addition to all the other stuff that’s being done by many other labs and

companies. I think the interactions between SMA researchers and SMA families is

one of the most exciting parts of my job. It permeates what I do every day, and

I try to instill that into the lab every chance I get.”

This research is an example of how the NextGen Precision Health Institute at Mizzou is expanding collaboration in personalized health care and the translation of interdisciplinary research for the benefit of society. Partnering together with government and industry leaders, the NextGen Institute empowers bold cross-disciplinary innovation and life-changing precision health advancement targeting individual genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors. The work of the institute is a cornerstone of the University of Missouri System’s statewide NextGen Precision Health Initiative.