Published on

Scientists find how nematodes use key hormones to take over root cells

Roger Meissen | Bond Life Sciences Center

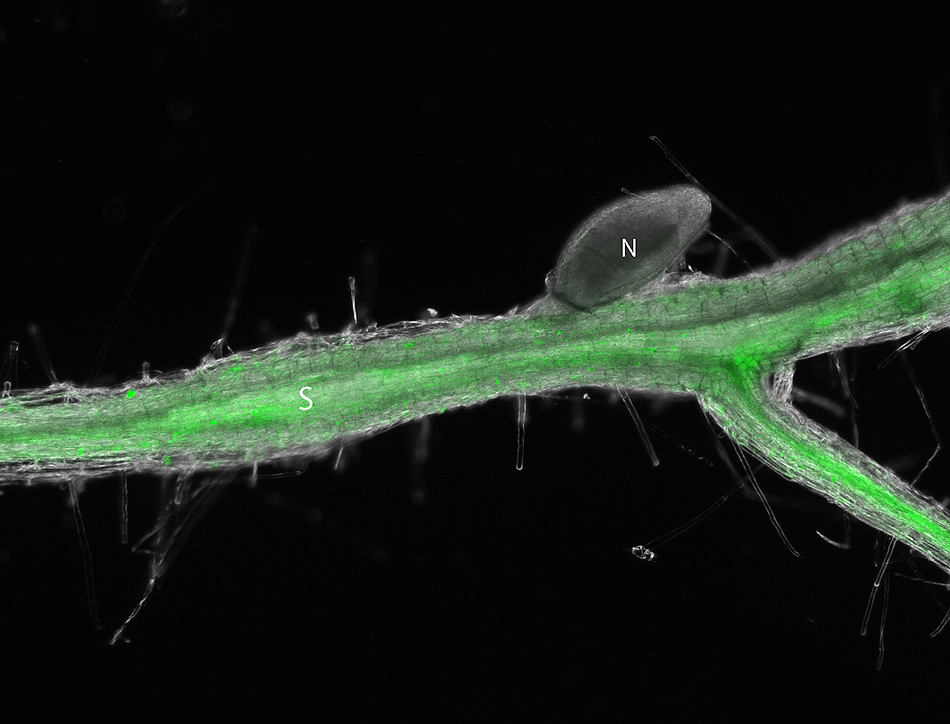

This Arabidopsis root shows how the beet cyst nematode activates cytokinin signaling in the syncytium 10 days after infection. The root fluoresces green when the TCSn gene associated with cytokinin activation is turned on because it is fused with a jellyfish protein that acts as a reporter signal. (N=nematode; S=Syncytium). Contributed by Carola De La Torre

This is a story about spit.

Not just any spit, but the saliva of cyst nematodes, a parasite that literally sucks away billions in profits from soybean and other crops every year.

Researchers are working to uncover exactly how these tiny worms trick plant root cells into feeding them for life.

A team at the University of Missouri Bond Life Sciences Center collaborated with scientists at the University of Bonn in Germany to discover genetic evidence that the parasite uses its own version of a key plant hormone and that of the plants to make root cells vulnerable to feeding. Their research recently appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Cytokinin is normally produced in plants, but these researchers determined that this growth hormone is also produced by nematode parasites that use it to take over plant root cells.

“While it’s well-known that certain bacteria and some fungi can produce and secrete cytokinin to cause disease, it’s not normal for an animal to do this,” said Melissa Mitchum, an MU plant scientist and co-author on the study. “This is the first study to demonstrate the ability of an animal to synthesize and secrete cytokinin for parasitism.”

Not Science Fiction

Reprogramming another organism might sound like a far out concept, but it’s a reality for plants susceptible to nematodes.

Cyst nematodes hatch from eggs laid in fields and quickly migrate to the roots of nearby plants. They inject nematode spit into a single host cell of soybean, beet and other crop roots.

“Imagine a hollow needle at the head of the nematode that the parasite uses to penetrate into the plant cell wall and secrete pathogenic proteins and hormone mimics,” said Carola De La Torre, a co-author of the study and plant sciences PhD student with Mitchum’s lab. “Nematodes use the spit to transform the host cell into a nutrient sink from which they feed on during their entire life cycle. This de novo differentiation process greatly depends on nematode–derived plant hormone mimics or manipulation of plant hormonal pathways caused by effector proteins present in the nematode spit.”

These effector proteins and other small molecules in their spit cause the root cell to forego normal processes and create a huge feeding site called a syncytium. In a short period of time, this causes hundreds of root cells to combine into a large nutrient storage unit that the nematode feeds from for its entire life.

Being able to convince a root cell to do the nematode’s bidding starts with a takeover of the plant host cell cycle — which regulates DNA replication and division. This implies that a plant hormone like cytokinin is involved, says Mitchum. Cytokinin normally regulates a plant’s shoot growth, leaf aging, and other cell processes.

Proving the relationship

While Mitchum’s lab had a hunch that cytokinin was key to this takeover, proving it took some creative science.

De La Torre and Demosthenis Chronis, a postdoctoral fellow MU at the Bond LSC depended on mutant Arabidopsis plants to explore the relationship. “One of the great things about using Arabidopsis as our host plant is the vast genetic resources of cytokinin and hormone mutants that are available through the scientific community,” De La Torre said.

She infected Arabidopsis that contained a reporter gene called TCSn/GFP with nematodes. This gene is associated with cytokinin responses within the plant cells and is fused with a jellyfish protein that glows green when turned on. So, De La Torre saw nematodes activated cytokinin responses in the plant early after infection when her plants emitted a green fluorescent glow under the microscope.

Next, she infected plants missing the majority of their cytokinin receptors with nematodes. Then she started counting nematodes present.

“After a careful evaluation of nematode infection, we observed less female nematodes developing in the receptor mutants compared to the wild type” De La Torre said. “The nematodes could not infect well, and that was a clear piece of evidence suggesting that cytokinin plays a main role in plant–nematode interactions.”

Another experiment looked at Arabidopsis containing a reporter gene called GUS that was fused to the regulatory sequences of the cytokinin receptor genes. All three cytokinin receptor genes were activated where the nematode was feeding.

A final experiment used a mutant that created an excess of an enzyme that degrades cytokinin, finding that a base level of plant cytokinin was also necessary for nematode growth.

“The simple statement is that the cytokinin receptors were activated in response to nematode infection and the mutants did not support growth and development of the nematodes,” Mitchum said. “This shows that if you take away the ability of the plant to recognize cytokinin the worms are unable to fully develop.”

An international collaboration

Mitchum’s team did not work alone.

The lab of Florian Grundler at Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-University of Bonn, Germany, was also on a mission to uncover if genes in the nematode controlled cytokinin activation. They had identified a key gene in the beet cyst nematode that makes the cytokinin hormone. When they took away the ability of the nematode to secrete cytokinin certain cell cycle genes were not activated at the feeding site and the nematodes did not develop. Now we know that the nematode is also secreting cytokinin to modulate the pathways.

De La Torre took that information and found the same gene in the soybean cyst nematode.

Now, Mitchum’s team is trying to find how this key gene might work differently in other nematode types, like root-knot nematode as part of a new National Science Foundation grant. They hope this will help lead to better resistance in future crops.

“Understanding how the nematode modulates its host is going to help us exploit new technologies to engineer plants with enhanced resistance to this terribly devastating pathogen,” Mitchum said. “Technology is changing all the time, we’re gaining new tools constantly, so you never know when something new is going to allow us to do something specific at the site of nematode feeding that will lead to a breakthrough.”

Mitchum is a Bond LSC investigator and an associate professor of Plant Sciences in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources. The study “A Plant Parasitic Nematode Releases Cytokinin that Control Cell Division and Orchestrate Feeding-Site Formation in Host Plants” recently was published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant #IOS-1456047 to Mitchum). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.